FSU researchers find most nitrogen in Gulf of Mexico comes from coastal waters

Almost all of the nitrogen that fertilizes life in the open ocean of the Gulf of Mexico is carried into the gulf from shallower coastal areas, researchers from Florida State University found.

The work, published in Nature Communications, is crucial to understanding the food web of that ecosystem, which is a spawning ground for several commercially valuable species of fish, including the Atlantic bluefin tuna, which was a focus of the research.

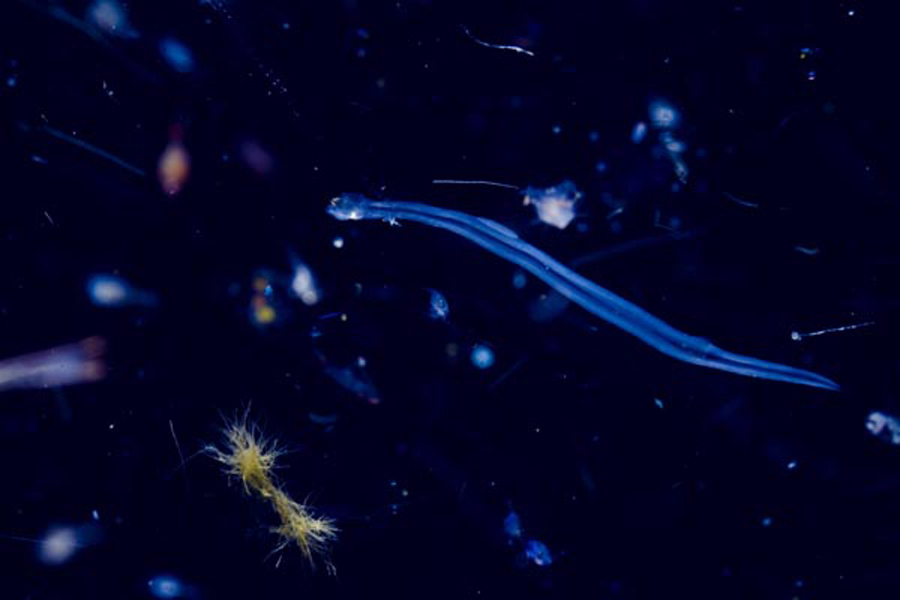

“The open-ocean Gulf of Mexico is important for a lot of reasons,” said Michael Stukel, an associate professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science and a co-author of the paper. “It’s a sort of ocean desert, with very few predators to threaten larvae, which is part of what makes it a good spawning ground for several species of tuna and mahi-mahi. There are all kinds of other organisms that live out in the open ocean as well.”

The food web in the Gulf of Mexico that supports newly born larvae and other organisms starts with phytoplankton. Like plants on land, phytoplankton need sunlight and nutrients, including nitrogen, to grow. The researchers wanted to understand how the nitrogen they need was entering the gulf.

They considered a few hypotheses. Their first idea was that nitrogen may have been coming from the deep ocean. Another was that a type of phytoplankton known as a nitrogen fixer was supplying the nutrient to larvae. Finally, they considered that nitrogen might be entering the open ocean from shallower areas of the coast.

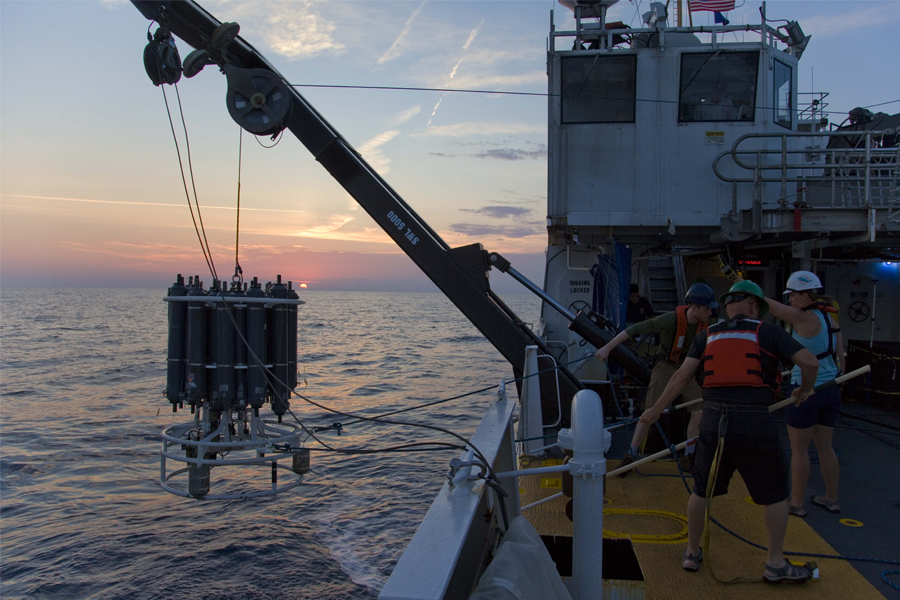

By combing measurements made at sea while on research cruises in 2017 and 2018 with information from satellite observations and models, they found that organic matter coming from the coasts is responsible for more than 90 percent of nitrogen coming into the open ocean in the gulf.

Scientists already knew that large, swirling eddies act like slow-moving storms in the ocean and move water from shallower areas near the coast into the interior of the gulf. The researchers believe the nitrogen is probably moved in those eddies, although they didn’t answer that question in this study.

Climate change is affecting how water near the surface of the ocean and deeper water mix. Understanding how a changing climate will affect these lateral currents is a harder question to answer.

It’s an important part of the ecosystem to understand because the survival of larval tuna and other species that reproduce in the open-ocean Gulf of Mexico is tied to currents that link coastal regions with the nutrient-poor open ocean.

“If we want to understand how this ecosystem will respond to future climate change, we need to understand how all of these lateral transports work in the ocean,” Stukel said. “Scientists studying biogeochemical balances — especially in basins enclosed by productive coasts, which is the situation in the Gulf of Mexico — should closely consider how lateral transport affects those ecosystems.”

This work was led by recently graduated FSU doctoral student Thomas Kelly. It was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, the National Science Foundation, NASA, the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory and the State of Florida. Researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the University of Hawaii at Manoa were co-authors on this study.