Chemical Conservation

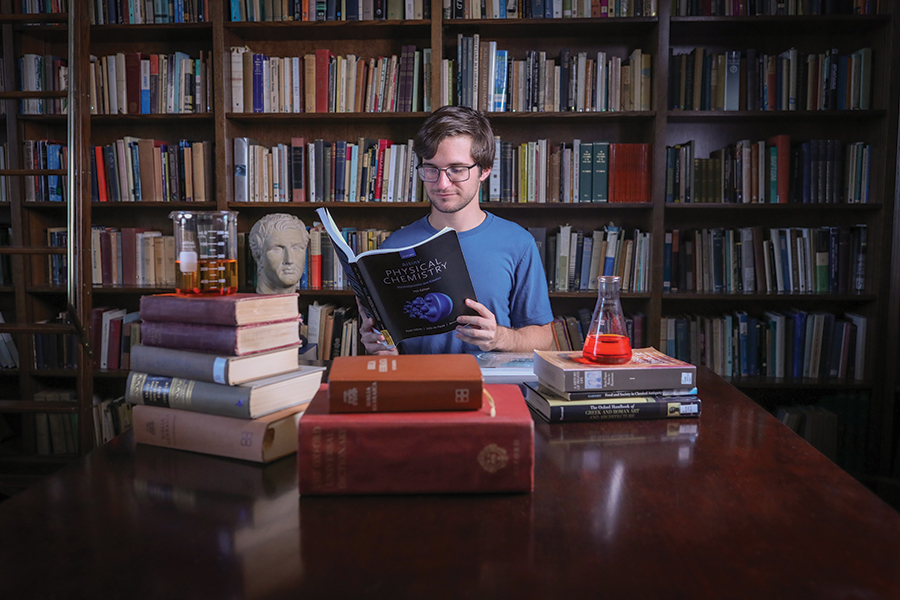

Double-major Jackson Cheplick uses research experience to prepare for a museum career

Van Gogh is an artist known the world over for his stunning landscapes, still lifes and portraits, but an element of his paintings, beyond visual style, sets his artworks apart on a chemical level — the cadmium in the yellow paint van Gogh used had an extra electron. For museum conservators, this compositional difference means van Gogh paintings must be cared for more frequently, as the oxygen in the air causes this particular yellow to chemically decompose, or oxidize, faster than the other colors.

While it may come as a surprise, this is why the world’s top museum conservators, professionals who restore and preserve priceless paintings and other artworks, are trained in chemical analysis. Florida State University junior Jackson Cheplick is frequently asked why he chose to double major in chemistry and classical civilizations and has become a pro at fielding the question.

“It is certainly not a traditional double major, but believe it or not, there is a connection between the two,” Cheplick said. “Art is composed of atoms and molecules just like everything else, and you can use chemical analysis to better understand ancient artifacts and art with the goal of conservation.”

For Cheplick, the pairing is the starting point for a career as a museum conservator. He plans to leverage his organic synthesis chemistry research and experience gained on an archaeological excavation experience in Italy to enter a specialized graduate program for future conservators.

While taking organic chemistry as a sophomore, Cheplick developed an affinity for the subject and connected with assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry Joel Smith who investigates efficient strategies to chemically synthesize some of nature’s most complex molecular structures.

“Jackson has an innate enthusiasm for chemistry that is unmatched by his peers,” Smith said. “He is a careful and diligent experimentalist who has a wont for learning, discovery and self-improvement. This curiosity is an unteachable quality central to the development of young scientists.”

The Smith Lab’s current goals involve investigating the potential of psychedelic molecules in the treatment of various neurological diseases and complex, organic marine matter’s potential to provide key insights for fundamental pharmaceutical discovery. Cheplick began working with Smith in early 2023, and his role at the lab involves creating the beginnings of chemical synthesis for further modification by Smith and graduate students.

“Jackson is a genuine individual with an unbridled proclivity for positivity,” Smith said. “Chemistry requires discipline and resilience, and Jackson exudes these qualities with the utmost integrity. I am confident that if he remains on current trajectory, he will be an exemplary FSU graduate destined to make a monumental impact through his multifaceted career goals.”

Over the summer, Cheplick took a brief break from his chemistry research to gain hands-on archaeology experience, adding to his unique skillset in both the arts and sciences. He joined the team conducting excavations at Cetamura del Chianti, a research site in Italy’s Tuscany region operated by FSU’s Department of Classics.

The Cetamura settlement, located in the mountains of Chianti, was occupied by three major groups in its history: Etruscans and Romans in antiquity and by Italians during the Middle Ages.

“Jackson took direction well, asked his supervisors insightful questions, and worked on his site with precision,” said Gregg Anderson, Cetamura advisory board member and a 1978 alumnus of FSU’s College of Communication. “He was also a good friend to his fellow students on the dig, many of whom did not know anyone else and had never traveled abroad.”

FSU faculty, staff, and students have studied the site for 50 years, aiming to uncover the realities of daily life during each period by examining a variety of excavated artifacts ranging from waterlogged grape seeds to pottery to the remains of a Roman bath.

“It was a great experience that I wish lasted longer than four weeks,” Cheplick said. “I am fascinated by learning how people lived in the past, and it was surreal to dig up pieces of history people built and interacted with hundreds of years ago.”

Taking inspiration from his classics and chemistry research, Cheplick is in the beginning stages of an Honors in the Major thesis, which will focus on using chemical analysis to uncover details held inside the ancient grape seeds. The waterlogged grape seeds found at Cetamura are one of the site’s most important discoveries; the water trapped in the seeds preserved them well enough for researchers to understand more about wine and culture in the ancient world.

Cheplick will examine both waterlogged and dried-out grape seeds found across a wide geographic area for his thesis, aiming to uncover more about the historical spread of grape seeds and wine-making practices in Western Europe. The project will also enhance his diversity of experience ahead of grad school.

“Whether you are in a lab working on chemical synthesis or in a museum working with artifacts, you need scientific analysis skills and a chemical intuition,” Cheplick said.