Recovery of endangered sunflower sea stars may play key role in restoring devastated submarine forests

Scientists working to understand the decimation of kelp forests on the Pacific Coast have found that the endangered sunflower sea star plays a vital role in maintaining the region’s ecological balance and that sea star recovery efforts could potentially help restore kelp forests as well.

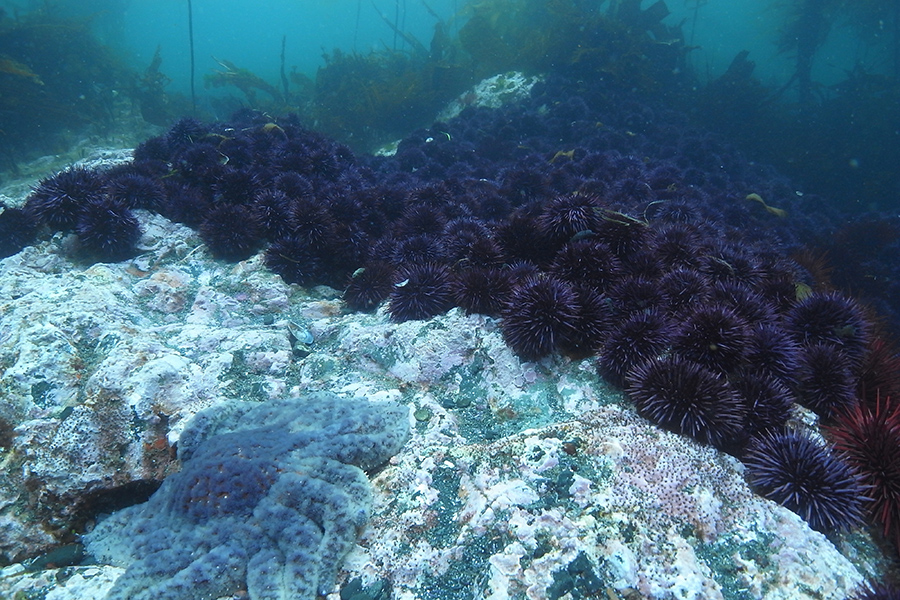

The multi-institution team, which includes Florida State University Assistant Professor of Biological Science Daniel Okamoto, has published a new study showing that a healthy sea star population could keep purple sea urchins — which have contributed to the destruction of kelp forests — in check.

Their work is published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“Our work is focused on understanding what factors maintain healthy kelp forests as well as healthy urchin populations,” Okamoto said. “That is, what scenarios lead to collapse versus coexistence of these important species.”

In recent years, sea star wasting disease, driven by rising water temperatures, has led to the species largely disappearing in its native ranges from Alaska to Baja, Mexico. This die-off is attributed as the cause for an explosion in purple sea urchin populations in many parts of the West Coast. Overgrazing by the urchins — along with warming sea temperatures — has led to the loss of kelp forests, which are among the planet’s most productive ecosystems and create suitable habitats that support the biological diversity and ecological wellbeing of coastal waters.

By combining data collection, and laboratory experiments and modeling to scale up the laboratory studies, the research team discovered that pre-disease populations of sunflower sea stars were likely able to control sea urchin populations through predatory behaviors. Sunflower sea stars can consume 0.7 sea urchins in a day, or five per week, and they will eat any urchin in their paths, whether the urchin itself is well-fed or a nutritionally poor “zombie” urchin.

“Even when we assumed the sea stars eat fewer urchins than we measured in the lab and explored various predation scenarios, we found that sunflower sea stars could keep sea urchin populations in check and support healthy kelp forests,” Okamoto said. “Our task now is to test whether these results hold in the wild. Out there, the behavior of sea stars and urchins may be quite different than in the lab. No model is perfect, but even when we were cautious, the results still indicated that sunflower sea stars play a critical role in keeping urchin populations in check.”

The relationship between sunflower sea stars, which are listed as Critically Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and sea urchins has never before been quantified.

“Until now, there have been no published studies testing the predation rates of sunflower sea stars on purple sea urchins, and thus no way to reasonably estimate the impacts of sunflower sea star predation on purple urchin populations,” said Aaron Galloway, associate professor at the University of Oregon Institute of Marine Biology and the study’s principal investigator. “This study addresses that gap, and the findings are significant and somewhat surprising.”

Restoring the sea stars, by captive breeding and translocation of the species as part of an active management plan, may be an important tool for regulating sea urchin population growth and encouraging kelp forest recovery.

“Species recovery is mission critical,” said Vienna Saccomanno, the study’s co-author and an ocean scientist at the Nature Conservancy. “It is time to take swift and decisive action toward recovering this iconic species to preserve biodiversity and further kelp forest restoration.

This study, funded by the Nature Conservancy and the National Science Foundation, was co-led by Galloway and Sarah Gravem from Oregon State University, with additional contributions by scientists from the University of Washington.

Visit the Nature Conservancy online to read more about this work.