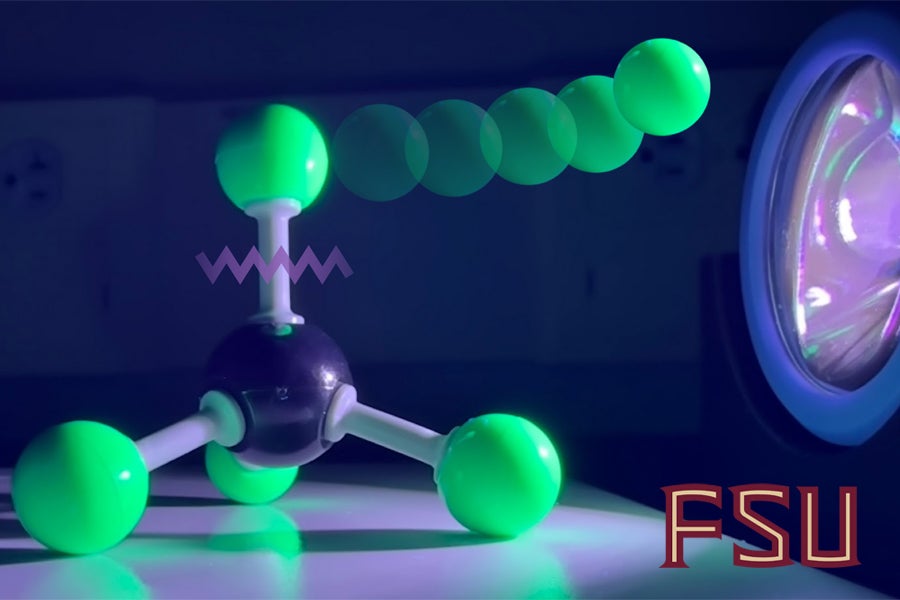

The FSU research published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society shows why: The molecule quickly moves into a less energetic state before the absorbed energy can break chemical bonds. The energy is drained too quickly into the wrong place, so bond-breaking is limited.

“Even though the molecule is absorbing the light and it’s getting the energy, it doesn’t always do the thing that you want it to do, which is to rip itself in half and catalyze some photochemical reaction,” said co-author Bryan Kudisch, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

How it works

When molecules absorb energy from light, that energy has to go somewhere. Sometimes it causes a chemical reaction. In other cases, it dissipates as heat or radiates light back; that is, it glows.

But ligand-to-metal charge transfer molecules didn’t behave as expected. When combined with other reactive materials and exposed to light, they produced chemical reactions, but at much lower efficiency than expected. They also didn’t radiate much heat or light. That posed a mystery: where was the energy from that light going?

The answer: the electron configuration within the material was moving. Instead of breaking chemical bonds, the electrons rearranged to move to a lower energy state.

“Whenever you give something a lot of energy, the thing that it wants to do is get rid of it,” said co-author Rachel Weiss, a graduate researcher. “The two ways that this system has is to either break the bond or rearrange its electrons, and it just tends to go in the rearranging pathway much more often.”

In the examples the researchers examined, molecules rearranged their electrons in about 85% of cases.