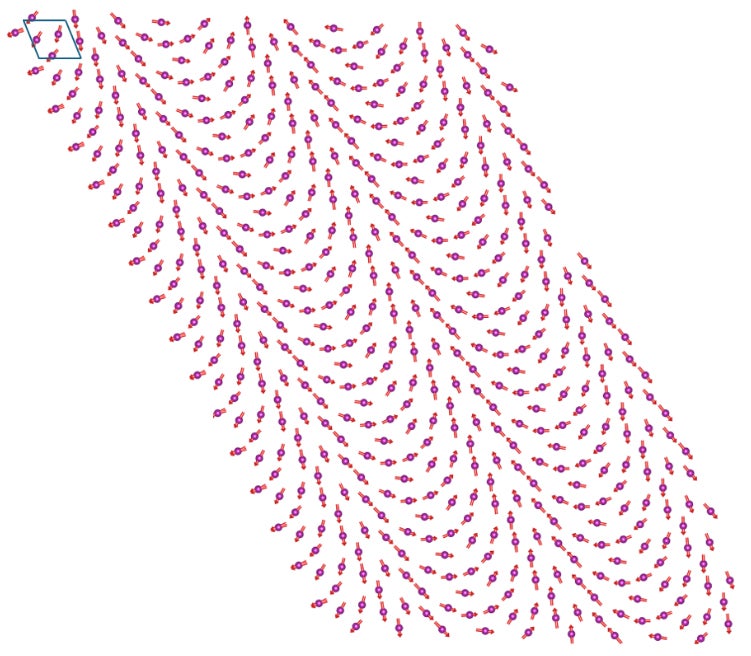

The FSU research team showed that their approach can be used to generate much more complex patterns of spins. These patterns are important because they determine a material’s overall magnetic properties. In contrast to the traditional magnets, the spins in this new material form repeating swirls, also known as spin textures.

How it works

The researchers combined two chemically similar compounds with different symmetries in their crystal structures. This structural mismatch leads to “frustration,” which indicates that both structure types become inherently unstable at the boundary between two chemical compositions.

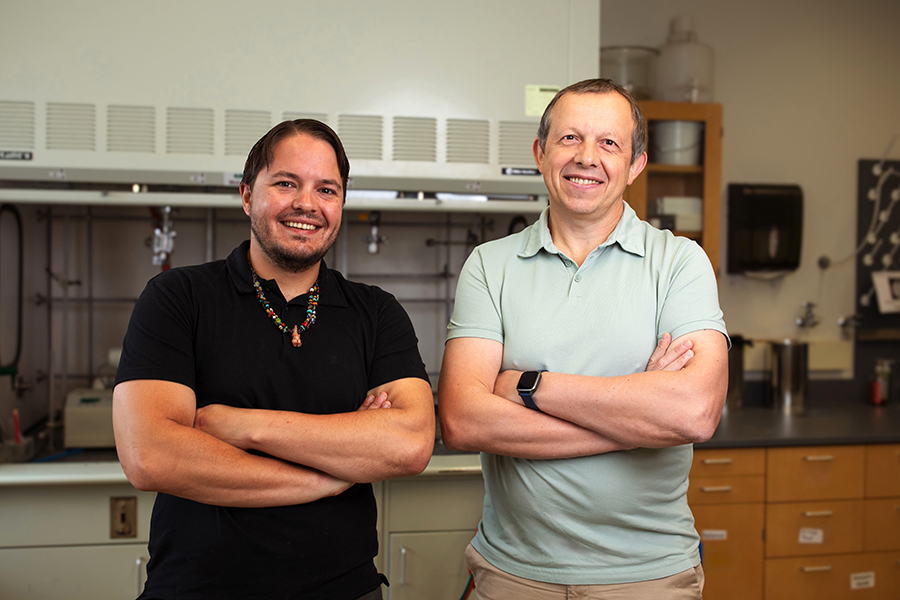

“We thought that maybe this structural frustration would translate into magnetic frustration,’” said co-author Michael Shatruk, a professor in the FSU Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. “If the structures are in competition, maybe that will cause the spins to twist. Let’s find some structures that are chemically very close but have different symmetries.”

They combined a compound of manganese, cobalt and germanium with a compound of manganese, cobalt and arsenic. Germanium and arsenic are neighbors in the periodic table.

After the mixture solidified into crystals, the research team examined the product and found the distinctive cycloidal spin textures that they were seeking. Such swirls of spins are known as skyrmion-like spin textures, and the search for more ways to find and manipulate skyrmion-hosting materials is a cutting-edge research area within chemistry and physics.

To determine this skyrmion-like magnetic structure, the team collected single-crystal neutron diffraction data on the TOPAZ instrument at the Spallation Neutron Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.