Florida State University and Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare team up to turn around COVID-19 tests in 24 hours or less

The longer a patient must wait for the results of a COVID-19 test, the less effective it is as a tool for preventing the spread of the disease.

Having to wait days to learn results means they could be out-of-date by the time they reach a patient. Long delays could also mean asymptomatic carriers are spreading COVID-19 in our community.

Florida State University is helping to contain the spread of the coronavirus by partnering with Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare (TMH) to create a temporary testing facility that will provide results in 24 hours or less.

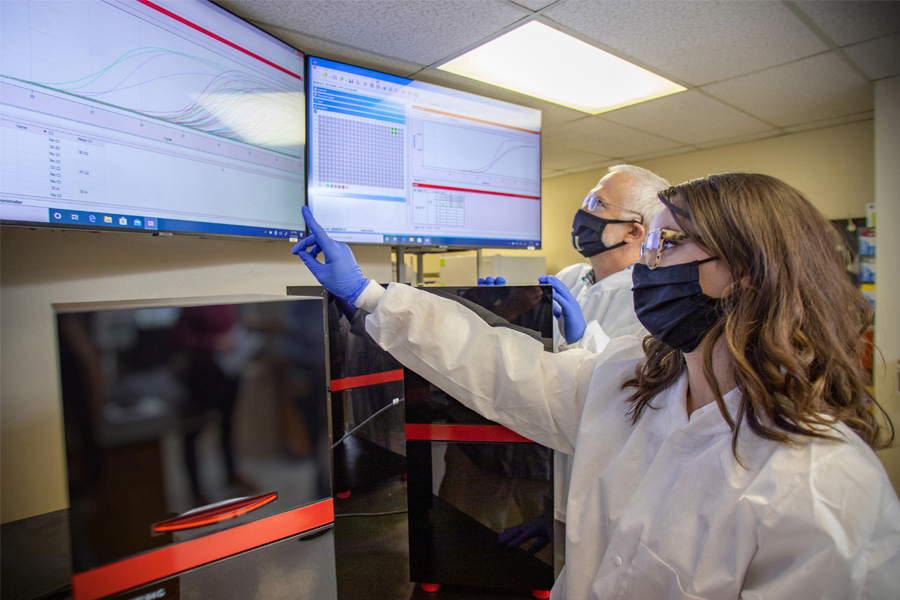

Using a new testing procedure developed by an associate professor in the Department of Biological Science, the TMH-FSU Rapid Response Laboratory is helping Florida State University to quickly identify and trace COVID-19 carriers in the university and Tallahassee community. TMH is providing lab personnel as well as billing patients.

“The ability to do this testing and quickly get results could be the difference in the ability to open things back up,” said Vice President for Research Gary K. Ostrander.

The lab will be an asset for FSU as it begins the fall semester, in addition to giving TMH some additional testing capacity for patients. The facility’s first samples came from TMH patients. When the lab is running at full capacity, it can process 1,000 samples in a day.

“As a leading research university, FSU brings resources to the table that will allow us at TMH to overcome supply limitations and provide for accurate and timely COVID-19 testing on a much larger scale,” said Mark O’Bryant, president and CEO of Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare. “The initial goal of this partnership was to match FSU’s intellectual and technological assets with our commercial and regulatory expertise. Once we have successfully accomplished that, we plan to work with other community businesses to make testing more readily available.”

Along with TMH, the Leon County Research and Development Authority also helped by connecting the project organizers with flexible space in an ideal location. LCRDA worked swiftly and efficiently with FSU and TMH to accommodate their needs to allow the lab to get up and running with minimal delay.

Florida State’s Fall 2020 plan includes baseline testing of students, faculty and staff as well as retesting and, in the case of positive tests, contact tracing and quarantine. An in-house lab will help all of that happen faster.

Picture this scenario: A student wakes up Saturday morning in a residence hall and feels ill.

“You’ve got to be able to find out very quickly if it’s COVID-19 or not, because if it is, you need to get them out of their residence hall, fraternity or sorority,” Ostrander said. “Because if that’s the case on a Saturday morning, by Saturday evening, you’re going to have a lot more sick people. That’s the whole point of why we did this.”

Or consider a visiting football team playing in Doak Campbell Stadium. On Friday afternoon, healthcare professionals can sample everyone associated with both teams and by bed check that evening, results are available.

The project is a model for how other universities without attached medical schools could create their own labs that can test for the coronavirus.

A laboratory requires what is known as a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certificate in order to test human specimens and provide patient-specific results to diagnose, treat or prevent disease. Florida State’s scientists don’t need this license for their usual research, but to test the FSU community for the coronavirus, they needed one, and quickly.

The Office of Research contacted TMH to inquire about partnering to establish a temporary site for coronavirus testing under the hospital’s CLIA certificate, and TMH agreed.

“As we look to repopulate the campus, the quicker we can get results, the better prepared we are to mitigate the spread of COVID-19,” said Audrey Wilson, an attorney for the Office of Research who negotiated and drafted the agreement between Florida State and TMH, as well as helped prepare the emergency use authorization required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. “The Department of Health and Human Services’ current pandemic policies presented an opportunity for this innovative partnership.”

The agreement created a way to legally test for the presence of the coronavirus, but the widespread nature of the virus in the United States has made testing supplies scarce and created longer wait times for results.

That supply problem was one that Jonathan Dennis, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Science, had been puzzling over for some time. He knew the supplies were available, just not in a format that others had considered.

To overcome that problem, Dennis developed a new testing procedure for the lab. By slightly altering the method and allowing the lab to use different materials than are typically used, he devised a way to get around the widespread supply shortage.

“Everyone is using a box mix of cake for this,” he said. “They’re pulling the Duncan Hines funfetti off the shelf. What do research scientists do? We don’t generally use those pre-made things. We buy flour and butter and eggs, and we make it. If Swans Down flour is not available, we can buy Gold Medal flour, and we know that it’s not going to make a difference to the cake.”

The procedure he created borrows from those used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. After samples are collected, the test measures whether it is possible to make copies of the collected viral genome using a technique called polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). If the procedure is able to copy a viral genome, that patient is positive. If not, the patient is negative.

The procedure can detect three separate parts of the viral genome. If two or three of the sections of each sample have the virus, it’s a positive. If just one part appears to have it, the lab considers it a possible positive and tests that patient again. The procedure is like running three tests in one for a single patient, but it still allows the lab to process samples quickly.

When the designers submitted their procedure to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization, they gave it the name “Observation of SARS COVID-2 Evidence by Objective Laboratory Analysis.” Take the first letter of each word and it spells “OSCEOLA.”

The name is the FSU research community’s tribute to the 19th-century Seminole leader, linking his leadership and unconquered spirit to this contribution to the ongoing struggle to contain the virus.

“Not only have we accomplished this, we’ve set up a model for how other people can accomplish this,” Dennis said. “We have thought at every juncture ‘What are we doing here and is this appropriate to relieve the testing problem that the nation has?’ And I think we have built something that can do that.”