Faculty Spotlight: Andrew Frank, Professor of History

Andrew Frank is the Allen Morris Professor of History in the Department of History, part of Florida State University’s College of Arts and Sciences.

the Department of History

Tell us a little about your background.

I grew up in South Florida and attended public schools in Broward County through high school. At the time, I never imagined that I would become a professor. I really didn’t know what I was going to do, but a career in journalism was near the top of a very long list of possibilities.

I went to college at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, where I had a few amazing history professors who changed my life. From there, I did my graduate work at the University of Florida and then took a decade-long tour of the country as a young professor, taking positions at the University of Massachusetts, California State University, Los Angeles, and Florida Atlantic University.

When did you first become interested in ethnohistory, particularly regarding the Seminole Tribe and the Native South?

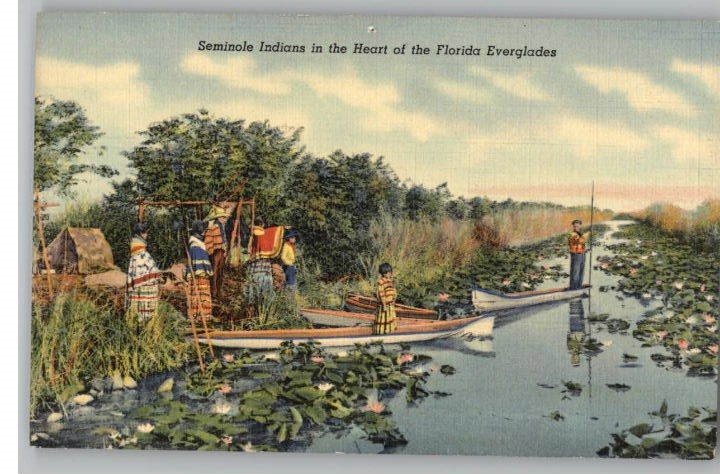

I became interested in the Native South a couple of years into graduate school. I entered a program that specialized in Southern history, and I kept asking questions about the past that I falsely presumed had little to do with Native people. These questions turned me into a specialist of the Native South. When I moved back to South Florida to work at FAU, I began to focus more specifically on the Seminole Tribe.

What are your current research interests, and what makes you passionate about them?

I am passionate about my research because it promises to help us rethink what it means to be a Floridian, Southerner and American. Each of my research projects addresses this issue rather directly, and these questions of modern identity are intricately connected to their histories.

My current research is largely about rethinking what the ongoing presence of Native Americans means to the history of the South and the United States. We have long understood the South to be biracial, but Native people have played and continue to play a larger overlooked or misunderstood place in that history.

Right now, I am writing two books. One is looking at the deep history that the Seminole Tribe has in Florida, a new look that emphasizes their deep roots rather than their history as newcomers. The other project is on the history and memory of Osceola. An important but not central player in the Second Seminole War, he became one of the most potent symbols of the abolition of slavery in the decades that followed. Unraveling this story is difficult but exciting.

What do you want the public to know about your research? Why is your topic important?

All non-Indians live on Native land. As much as our nation’s history has had moments of great transitions, this history has been a continuation of an indigenous history that predates the arrival of the Spanish to St. Augustine, the English to Virginia, or the Puritans to Massachusetts. Recognizing this rather simple idea, I think, can help us reimagine how the United States came to be and what it means to be an American citizen.

My latest book (“Before the Pioneers”) looks at the ways that the Tequesta and Seminole Indians were central to the development of Miami in the centuries and decades before Henry Flagler came to South Florida. Without the early development, South Florida would look remarkably different today.

Who are your role models? Who has influenced you most in your life?

I have many role models and influences, individuals who have taught me the importance of being a generous and inquisitive person. My parents taught me the value of education for its own sake, and they had me asking questions with ambiguous answers from a very young age. At the same time, they urged me not to just focus on school but to work in ways to help others.

I also had an amazing graduate adviser, Bertram Wyatt-Brown, who did more than teach me how to be a historian. He taught me that excellence as a scholar should not come at the expense of having good friends, a loving family, and interests outside of work.

My wife, also a historian, continues to be an intellectual and personal role model for me.

What brought you to Florida State University? Why do you enjoy working at FSU?

I was happily employed at FAU for several years when the FSU job opened. I was hesitant to leave friends and family and a great department. FSU offers so many unique advantages for me. I had been to Tallahassee dozens of times before moving here in order to do research at FSU or the State Archives, and I can think of no better place to study and teach the history of the Seminoles than FSU. The university’s connection with the Tribe and the interests of many students in its history makes for a really unique experience.

What is your favorite part of your job?

My favorite part of my job is having the opportunity to bring my research into the classroom. Publishing research is a slow process, and having the ability to share and refine it in the classroom compensates for my general impatience. At the same time, my research is better because of my students. They insist that I connect and explain evidence carefully, and they see interpretations and details that I often miss. I am a better writer and scholars because of them.

What is the most challenging part of your job?

There is never enough time to do everything. I have great resources and smart students, and therefore I confront new questions all of the time that I will never have time to address.

How do you like to spend your free time?

I have three kids who keep my busy with various activities. They all love to act (they did not get that from me), so I spend a lot of time at Tallahassee’s Young Actors Theatre. I’m also a slow but avid runner.

If your students only learned one thing from you (of course, hopefully they learn much more than that), what would you hope it to be?

Hopefully all of my students will learn that everything has a history, and that every generation of historians must ask new questions about the past in order for it to be relevant to their lives.