Crucial Context

Anthropologist Choeeta Chakrabarti examines how societal structures can impact health outcomes in marginalized communities

Not all anthropologists spend their careers excavating ancient remains and searching for remnants of histories and peoples past. Medical anthropologists like Choeeta Chakrabarti work in the present, stepping into hospitals, rural villages, and even private homes to investigate the social and biological elements that influence a population’s wellness.

Chakrabarti, an assistant professor in the Florida State University Department of Anthropology, works to connect the dots between social inequality and health outcomes among some of India’s most marginalized communities. In her research, she explores how human health is influenced by a complex interplay of physiological, cultural and environmental factors.

“We have a tendency to think of health as a result of individual choices, such as unhealthy eating habits or not taking vitamins,” Chakrabarti said. “We put the blame on individuals without recognizing that, beyond biology, there are social structures in place that influence health outcomes. You need that perspective to address the root causes of health issues.”

Following a lifelong interest in medicine, health and people, Chakrabarti received her bachelor’s in biotechnology from Osmania University and her master’s in sociology from the University of Hyderabad, both in India, before completing her doctorate in cultural anthropology at the University of Florida in 2018. She joined FSU in 2020 as teaching faculty and became an assistant professor of anthropology in 2023.

“One of my core missions is to ensure that marginalized communities are seen and heard and that their struggles are addressed with the respect and dignity they deserve,” Chakrabarti said. “I spent three months immersed within the Dalit manual scavenging community in Dharavi, Mumbai, India, an area considered Asia’s largest slum.

“Dalits are a group formerly known as ‘The Untouchables;’ they exist outside the traditional caste system, occupying the lowest and most marginalized stratum of Indian society. Untouchability is no longer practiced in such overt ways, particularly in urban areas. However, it persists in more insidious forms where discriminatory practices continue, but caste is no longer explicitly acknowledged as the cause.”

Chakrabarti studied manual scavengers, individuals who clean up human waste, often bare-handed. For women, this can involve emptying outdoor toilets, known as dry latrines, into baskets, which they carry for long distances balanced on their heads. For men, the work is more physically dangerous and routinely involves entering septic tanks without personal protective equipment — often without clothes — to remove clogs, exposing them to risks such as suffocation from toxic gases.

Construction of dry latrines and employment of manual scavengers was banned in India in 1993, and several laws have since expanded and strengthened the ban, the most recent being in 2013. Dalits are born into the caste system with untouchable status that condemns them to the most degrading jobs, including manual scavenging. The work reinforces their exclusion and perpetuates their untouchability, trapping them in a cycle of discrimination.

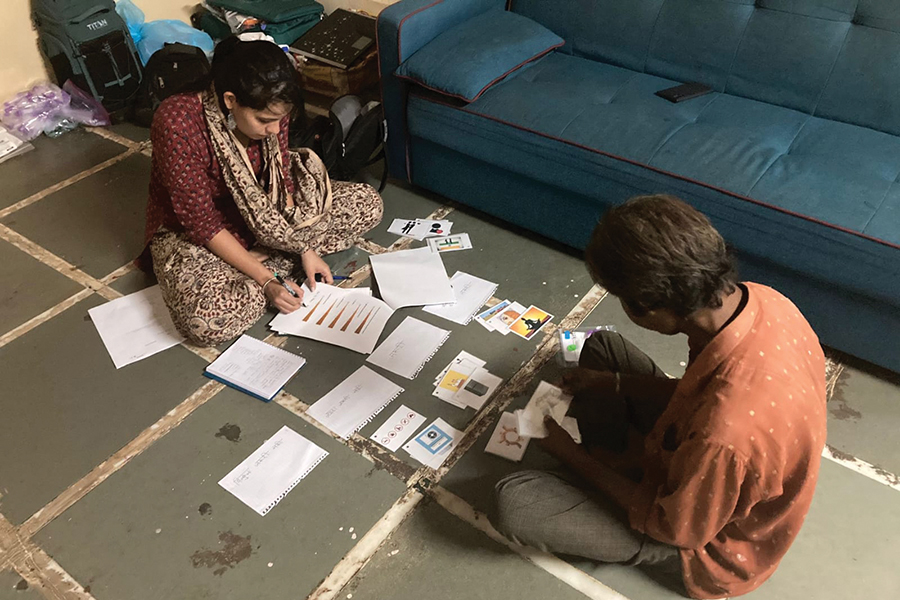

Chakrabarti’s time with this community involved both understanding the harsh realities of their work and getting to know them as individuals. This research was conducted in collaboration with Safai Karmachari Andolan, a grassroots organization dedicated to eradicating manual scavenging and rehabilitating those engaged in this work. In interviews, she queried about their personal stories, when and how they fell in love, and childhood dreams, conveying their humanity alongside their struggles.

“I find fieldwork and the opportunity to engage directly with communities incredibly fulfilling,” she said. “It’s not easy because you witness challenges firsthand that take a toll on you and force you to confront your privilege and its implications in comparison to the people you’re working with. It helps to ground your research in reality — it’s humbling and rewarding.”

Preliminary results from Chakrabarti’s work in Dharavi show correlation between loneliness and alcohol consumption among Dalits who worked as manual scavengers. Chakrabarti paired psychometric evaluations assessing depression, anxiety, alcoholism, and loneliness with cortisol testing and saliva and hair analyses to examine the physical toll scavenging takes on immune function and health. This biomarker research is conducted in collaboration with K. Ann Horsburgh, a biological anthropologist and associate professor also in the FSU Department of Anthropology.

“Choeeta’s curiosity is bottomless,” said Mark McCoy, professor of anthropology and department chair. “She’s interested in everything. That, combined with her empathy, makes her an outstanding researcher and someone who excites students to learn more about the world.”

Back at FSU, Chakrabarti teaches topics ranging from the history of anthropology to gender-based violence, and she hopes her students walk away with a desire to learn more and convey the humanity of the people and histories they encounter, something that carries into her own work.

“My work allows me to amplify voices of communities that are usually silenced,” Chakrabarti said. “It may take decades for a systemic change, but I know I’m advocating for and working toward a solution today.”

Dena Reddick is an FSU alumna who earned a master's degree in history in May 2020.