Iceland to FSU (and back)

Icelander Benedikt Jóhannesson always knew he would return to his homeland after his education in the United States and he has had a successful career there as a publisher, businessman and, most recently, a political leader.

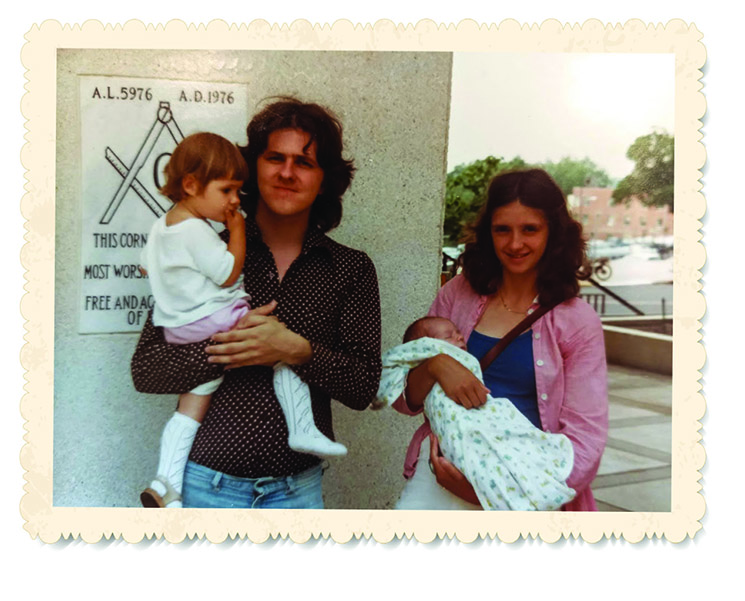

But he still carries fond memories of his years earning his master’s degree and Ph.D. in Statistics at Florida State University. He and his wife came to Tallahassee in January 1978, and by the time they left, the first two of their three children had been born.

Although he chose Florida sunshine to warm up from his undergraduate experience at the University of Wisconsin, his first reason to come to FSU was the stellar reputation of its Department of Statistics.

“It was considered one of the 10 best in the U.S. at the time,” he recalled. “Almost all of the world-famous statisticians came to Tallahassee” when he was a student. After spending a postdoctoral year in Montreal, Jóhannesson and his family settled in the island nation of Iceland, which is the size of Kentucky with a population — 348,000 — a bit smaller than Tampa.

The now-63-year-old started out teaching at the college level and moved on to consulting, first in statistics and later actuarial and economics work. In the early 1990s, he founded a company that published periodicals on economics and business, adding titles over the next 25 years.

“In the beginning they were business- and economics-oriented magazines, but then I added a number of publications on travel and nature in Iceland,” Jóhannesson said.

Iceland was hit particularly hard during the worldwide recession, beginning in 2008 when all three of its major banks went bankrupt.

“The Icelandic currency, the krona, was devalued by more than 50 percent in one day,” Jóhannesson said. “Many listed companies went bankrupt — only about two or three survived in the same form. One of the few companies that survived was a technology company I led as chairman. The crises hit Iceland hard. People lost a lot of money; a lot of people lost their jobs.

“Many people had loans indexed to foreign currency … I think this the only country where all the loans that people owed went up almost immediately by 10, 20 or even 50, 60 percent … and that was a shock to people. There was quite a bit of misery in the country.”

Saved by a volcano

Surprisingly, tourism helped the Nordic nation emerge from the recession. In April 2010, Iceland’s Eyjafjallajokull glacier volcano erupted. A cloud of ash drifted eastward toward Europe, causing cancellations of 100,000 flights over eight days.

“People were depressed at the time, but it turns out that it was probably the best marketing for Iceland. A lot of journalists came here. Of course, they couldn’t just write about the eruption, so they sent pictures from all over the country, and that helped us. Iceland is a beautiful country,” he said.

In fact, 92 percent of respondents to a survey from the Icelandic Tourist Board said nature — the Northern Lights, the beautiful, unspoiled and scenic land, geysers, glaciers, black-sand beaches, natural baths and waterfalls — was their reason for visiting. Since 2010, the number of annual foreign visitors has nearly quadrupled, to more than 2.2 million.

“We probably would have recovered anyway, like most of the other countries hit by the recession, but it certainly went faster with the tourism boom. If you go through the center of Reykjavik you’re more likely to hear English, German or Chinese spoken than Icelandic,” Jóhannesson said.

Like those tourists, Jóhannesson enjoys hiking and mountain climbing in his spare time. He’s cosmopolitan — speaking Danish, German and “a little French” in addition to English and Icelandic — and enjoys travel.

“Just this year I’ve been to Uganda, I’ve been to Israel, I’ve been to Russia, and actually many countries in Eastern Europe,” he said. “I’ve been to Switzerland. Mostly for fun. I’ve had more free time after I stopped being minister, and I decided to use it wisely. Who knows when I will have time to do all that again?”

A foray into government

Jóhannesson was the founder and first leader of the Liberal Reform Party in 2016, was elected to Iceland’s parliament and served as the nation’s minister of finance and economic affairs between 2016 and 2017.

In American terms, Iceland would be considered “socialist,” with health insurance for all, strong pension funds, a fairly equitable distribution of wealth and a minimum wage that equals nearly $3,000 a month. A respectable sum, but according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Price Level Index, it is the third-most expensive country in the world.

“Part of the reason is that we are a relatively closed society for importing agricultural products,” he said. “We could be cheaper if we opened up more.” A plank of his party’s platform is to encourage free trade and liberal — in the U.S. sense of the word — social ideals.

“In that respect, we want to move closer to European countries, and we have advocated joining the EU and the euro,” he said of his party. But partly because of Brexit, any thoughts of joining the European Union “unfortunately are not active at the moment.”

“As international students, we were always quite welcomed by the university and the local community.”

— Benedikt Jóhannesson

While there are stories of Icelanders being Vikings, “actually we have evolved into a peaceful people,” he said. “We were never at war.You can safely say that we are pro-peace —I think probably all the political parties subscribe to that idea.”

Today, Jóhannesson said, “I write a lot. Articles on politics and economics, and sometimes I write short stories also,” including a collection written in Icelandic.

Benedikt Jóhannesson, wife Vigdís, daughter Steinunn and son Jóhannes are pictured in Tallahassee in 1980. Courtesy photos.