In research published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, Diamond and FSU Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science graduate student Lilli Boss showed that new fuel regulations that cut sulfur by about 80 percent also lowered cloud droplet formation by about 67 percent compared with earlier, dirtier fuels.

“The unexpected rerouting of global shipping gave us a unique opportunity to quantify aerosol-cloud interactions, reducing the largest source of uncertainty in global climate projections,” said Diamond. “When your ‘laboratory’ is the atmosphere, it’s not every day you can run experiments like this one. It was an invaluable opportunity to get a more accurate picture of what’s happening on Earth.”

The findings could help refine global climate models, offering policymakers and scientists more accurate climate predictions and insight into how environmental policy can protect human health.

CLEANER FUEL, FEWER CLOUDS

In January 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) mandated a major reduction in sulfur content in marine fuels to decrease air pollution. Aerosols from ship emissions, especially sulfate, influence cloud formation and brightness, which in turn affect Earth’s energy balance. Referred to as aerosol-cloud interactions, these particles cause clouds to form with smaller, more numerous droplets, making them brighter and thus more reflective of sunlight. This creates a cooling effect, which has historically masked about one-third of the warming caused by greenhouse gases.

But air pollution’s effects are marked by huge uncertainty and variability. Unlike long-lived greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, or CO2, which linger in the atmosphere for centuries, aerosols stay only for days or weeks. This short lifespan, coupled with the unpredictable nature of clouds, makes aerosol-cloud interactions the single largest source of uncertainty in global climate projections.

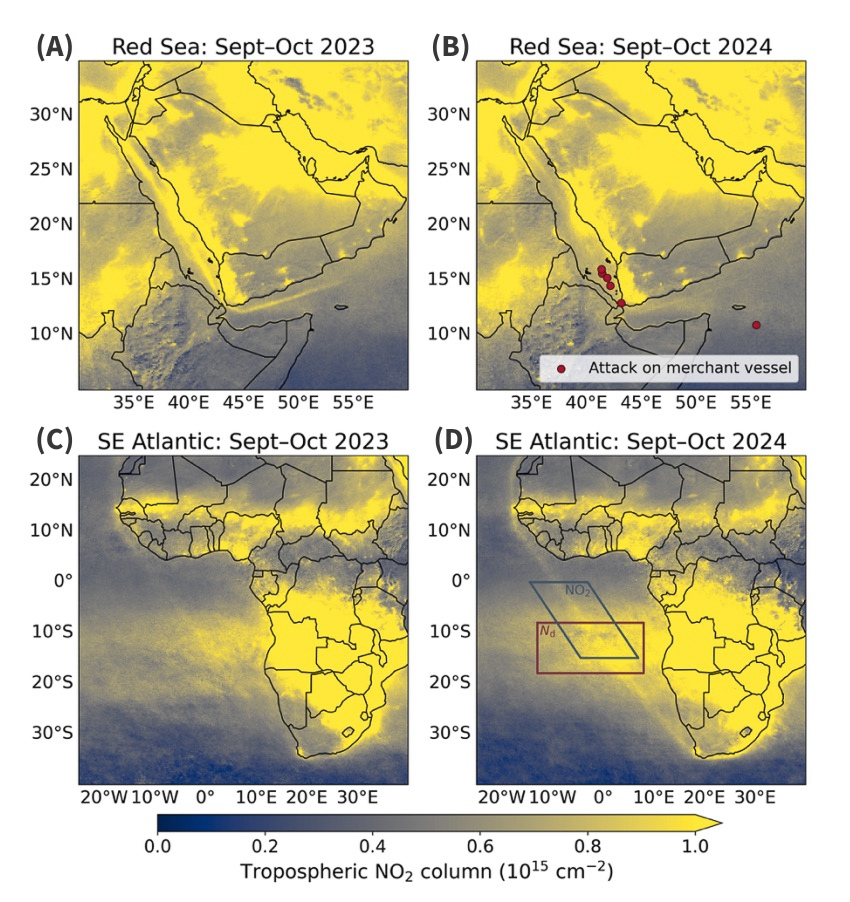

Diamond’s previous research had shown that clouds in major shipping corridors were forming with larger and less numerous droplets after IMO 2020. Scientists are currently debating what role the resulting increase in sunlight absorbed over the ocean played in the 2023 and 2024 marine heatwaves in the Atlantic Ocean. Different groups also disagree about how much cloudiness declined after IMO 2020, with estimates ranging from a relatively small 10% change to a massive 80% decrease.