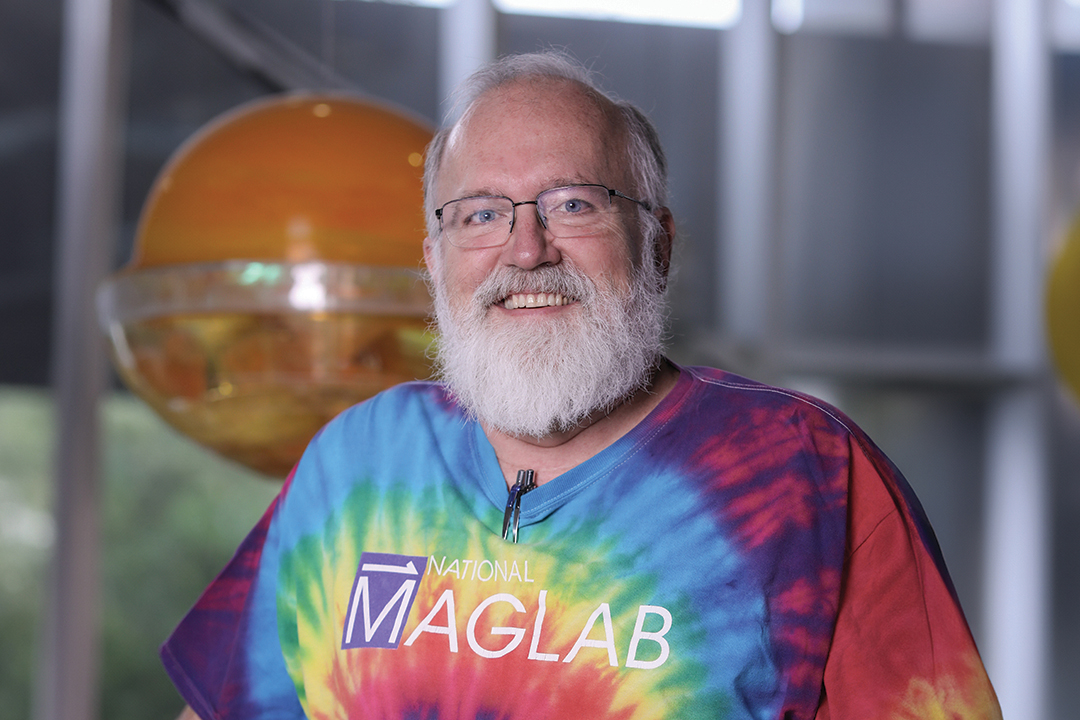

Magnet Man

Physicist Greg Boebinger reflects on a career of discovery and science education

Thanks to cellphones, there is a world of information available at our fingertips. Mobile devices have become a ubiquitous tool in modern society, yet many of the materials used to create that technology didn’t even exist 30 years ago.

Physicists like Greg Boebinger, Florida State University professor and former director of the FSU-headquartered, National Science Foundation-funded National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, are among the researchers behind the materials that comprise today’s technology and those investigating the potential of the most powerful magnets in the world to make tomorrow’s inventions possible. High magnetic fields allow researchers to push the boundaries of materials ranging in conductivity, from the semiconductors used to make cellphones to the superconductors used to power MRI machines.

“Since pursuing my bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, I was always interested in the scientific research that underpins engineering, which led me to study physics and high magnetic fields,” Boebinger said. “My research primarily investigates the strange new properties that emerge when electrons work together in a variety of conductive materials under the forces of intense magnetic fields.”

Protons, neutrons, and electrons are the particles that form atoms composing the known substances that make up our observable universe. When electrons are activated to conduct heat or electricity, they behave in unique collective ways similar to how a school of fish works and moves together. According to Boebinger, understanding variations in the collective behaviors of electrons is key to explaining superconductivity, a property of certain materials to conduct electricity without energy loss when they are cooled. Superconductivity remains one of the biggest mysteries in condensed-matter physics.

“Greg is a renaissance person in science — he never ceases to learn and to communicate science in every area the MagLab pursues, knowing every electrical component and person who works there.”

— Laura Green, National High Magnetic Field Laboratory chief scientist

“Because high magnetic fields are the gentlest way to destroy superconductivity, we apply these powerful magnets to superconductors to see what aspects of those materials make them a superconductor when we turn the magnetic field off,” Boebinger said. “My 1990s experiments using this strategy were some of the pioneering efforts that led several other researchers to now follow this method, with many coming to the MagLab to perform their experiments. It’s become a wonderful community of scientists.”

After earning his doctorate in physics in 1986 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boebinger spent a year as a NATO postdoctoral fellow at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, France. He joined Bell Laboratories in 1987 to establish a new pulsed magnetic fields research facility. In 1998, Boebinger became head of the National MagLab’s Pulsed Field Facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory near Santa Fe, New Mexico, and in 2004, he moved to FSU to begin serving as the director of the National MagLab with responsibility for its headquarters at Florida State University, along with campuses at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the University of Florida.

Boebinger served as the National MagLab director for two decades while continuing his own research using magnetic fields to investigate superconductivity and related physical phenomena. He has pursued a lifelong journey exploring the fundamental physics underlying the properties of high-temperature superconductors while also facilitating technological development and prioritizing communication of this work to the public.

“Science communication is important because it’s valuable to understand that the economic prosperity we enjoy today frequently results from scientific research that leads to engineering developments that directly impact our lives,” said Boebinger, who often eschews a suit and tie in favor of tie-dye t-shirts for public events to help make himself more approachable. “The MagLab puts on an annual open house that hosts up to 10,000 individuals wanting to learn more about high magnetic fields research; it’s my favorite event all year.”

In 2021, Boebinger was elected by his peers to one of the highest honors a scientist can receive — membership in the National Academy of Sciences, which was established by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 to provide independent, objective advice to the nation on matters related to science and technology. He is also a fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Now that he has more time for research, Boebinger plans to propel his field toward an explanation of high-temperature superconductivity by conducting new experiments and attending more conferences to discuss the latest advances with experimentalists and theorists.

“Greg is a renaissance person in science — he never ceases to learn and to communicate science in every area the MagLab pursues, knowing every electrical component and person who works there,” said Laura Greene, National MagLab chief scientist, FSU’s Marie Krafft Professor of Physics, and an NAS member. “He's constantly encouraging our scientists across diverse facilities to create important synergy, and I believe Greg is one of the great scientific leaders of our time.”