From sea to sky

Tropical cyclone formation. Paleoclimatology. Ecology and biology of deep-sea organisms. Conservation. Geochemistry. Microbial ecology.

Faculty in Florida State’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science are conducting world-class research on these subjects and more, and expanding knowledge of the Earth, air, water and the life that inhabits them.

Part of the department’s recent success is being driven by intense interdisciplinary collaboration pursued by some of its newest members — six young women hired since 2008 who have accounted for more than $3 million in grant funding over the past five years and whose research is critically relevant as activists and legislators take steps to address climate change.

When it comes to EOAS, “I think our department is among the big dogs in our field,” said associate professor of biological oceanography Amy Baco-Taylor. “We have really high-quality faculty in all three fields.”

Looking to the deep

Baco-Taylor’s research centers on ecology and biology of deep-sea organisms, and the questions she asks inform conservation and management of deep-sea species. Humans now impact nearly the entire ocean — trawling, a destructive fishing method that scrapes across the sea floor as far down as 3,000 meters or nearly 10,000 feet is among the biggest — so much of her recent work is focused on seamounts and deep-sea corals.

“Seamounts have specialized communities of deep- sea corals, sponges and other organisms. In some areas, they can form reefs or dense coral forests — and because they make that structure, seamounts act as a habitat for a variety of invertebrates and fish,” Baco-Taylor said. “But a lot of these organisms are slow growing — microns per year — and a lot of them are long-lived. If fishermen destroy that with a trawl, it may never recover.”

Phytoplankton’s key role

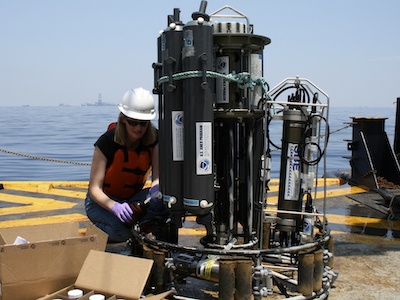

Geochemist and assistant professor of oceanography Angela Knapp examines the health of the oceans by studying the nutrients that fuel phytoplankton growth. She recently served as chief scientist on a research cruise in the Gulf of Mexico aimed at understanding nutrient addition and limitation, which could identify nutrient sources fueling red tides on the West Florida shelf.

“We care about phytoplankton growing in the ocean because they play an important role in regulating atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, and CO2 in the atmosphere plays an important role in regulating climate,” Knapp said. “We also think plant growth in the ocean is limited by nutrient availability, so my research focuses on identifying and quantifying the role of different nutrients supporting phytoplankton growth and how that influences climate.”

Lessons from the past

Assistant professor of oceanography and meteorology Alyssa Atwood studies paleoclimatology to develop records of past sea surface temperature and rainfall patterns in the tropics based on the chemical composition of coral skeletons and mud, and examines climate extremes associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation. Her research centers on the Pacific Ocean, which serves as one of the planet’s largest heat engines — taking in solar energy and redistributing it around the globe.

“What happens in the tropical Pacific affects temperature and rainfall patterns across more than half the globe, and this changes every few years through ocean temperature variations associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation,” Atwood said. “Studying past variations may help us understand how it is likely to change in the future.”

The birth of tropical cyclones

Atmospheric variation impacts the formation of clouds and cyclones in tropical regions, which are part of assistant professor of meteorology Allison Wing’s research. She analyzes how and why tropical clouds clump together and the effect storms have on the larger climate system, as well as why the number and strength of tropical cyclones varies year to year. On her radar is one of the biggest open questions in tropical meteorology: What controls how many tropical cyclones form across the world in a given year?

“Around 90 form globally per year, but we don’t know why it isn’t nine or 900,” Wing said. “I study the basic physics of tropical cyclone formation to try to make progress on this question. In addition to scientific curiosity, I’m motivated by the pro- found impact tropical cyclones and other weather and climate phenomena have on our society. It is of utmost importance for us to understand, so we can help people be more prepared.”

Effects of the ‘unseen majority’

From natural to man-made disasters, associate professor of oceanography and microbial ecologist Olivia Mason studies bacteria and archaea (microbes) in the ocean and in coastal terrestrial environments. Her research focuses on how microbial communities respond to ecosystem disturbances, such as oil spills and low oxygen conditions, as well as the ecological consequences of this response.

“Often referred to as the unseen majority, microbes serve in important functions, such as production of life-sustaining oxygen, filtration of nutrients in salt marshes, minimization of harmful algae blooms, and consumption of oil,” Mason said. “My research revealed which microbes were abundant and active, and what oil constituents the dominant uncultured microorganisms consumed, during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, leading to a greater under- standing of the ecological impact of oil spills.”

A focus on conservation

While Mason examines microscopic organisms, assistant professor of oceanography Mariana Fuentes’ research addresses questions that are advancing conservation and management of marine megafauna, specifically sea turtles, although she has students working with dolphins and sharks as well.

Some of Fuentes’ work aims to ascertain the best allocation of resources to maximize conservation outcomes, or to identify where to place marine-protected areas to shelter certain species. Other aspects consider the spatial ecology of species to examine where species and areas of threat coincide.

“One of my projects looks at the impacts of vessel strikes on sea turtles, and for this we need to determine the spatial extent of both sea turtles and vessels to identify areas where they overlap,” Fuentes said.

A gradual shift

Because FSU is a Research I institution, responsibilities of EOAS faculty include teaching undergraduate and graduate classes, advising students, doing service both at FSU and in the broader scientific communities, and engaging in scientific research at the highest level.

And while their main emphasis is on the research, these faculty members are also quietly helping to turn another tide — the underrepresentation of women in the sciences. Just eight of the department’s 43 faculty members are women.

“For decades there’s been equity in female undergraduate and graduate student levels, but then there’s the leaky pipeline, there’s falloff at the postdoc and faculty stages,” Knapp said.

Fuentes, who joined FSU in 2015, noted that most of the women on staff are at the junior level, but she expects them to climb the ranks. “When I came here, I saw the department was heavily male dominated, but that’s changing, and it will continue to change,” she said. “You can see that shift happening.”