FSU’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Institute celebrates 50 years of pioneering research

For half a century, the Florida State University Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Institute (GFDI) has been a global leader in the study of fluid flow and motion — the ways that the circulation of liquids and gases influence our oceans, atmosphere and groundwater.

Since its start in 1967, the GFDI has cemented its position as the gold standard in its field, producing foundational research and core theoretical paradigms that have shaped scientific thinking about fluid dynamics in far-reaching and fundamental ways. This year, as the institute celebrates its 50th anniversary, that momentum of research and discovery continues apace.

“The GFDI has been an outpost of excellence in the study of geophysical fluid dynamics,” said Kevin Speer, GFDI director and professor of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science. “I don’t think any other organization in the region has had the impact on the field that this institute has had.”

Established in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Defense, the founding mission of the GFDI was to pursue a more realized understanding of how large-scale atmospheric waves influence weather patterns.

The GFDI set out to demystify the properties and dynamic behavior of these massive atmospheric waves and currents. Under the leadership of its founder and original director, former FSU Professor Richard Pfeffer, the GFDI began conducting revolutionary research practically from the moment of its inception.

“I’m always amazed when I look back — the founders described problems that are still important now and means of finding laboratory models for these problems that are still state-of-the-art,” Speer said. “There were fundamental insights into nature developed in those early stages that continue to be relevant.”

Early GFDI researchers addressed big picture questions like baroclinic activity and weather patterns, as well as more localized concerns like the collapse of underwater caves and the sinkholes that pepper Florida’s landscape.

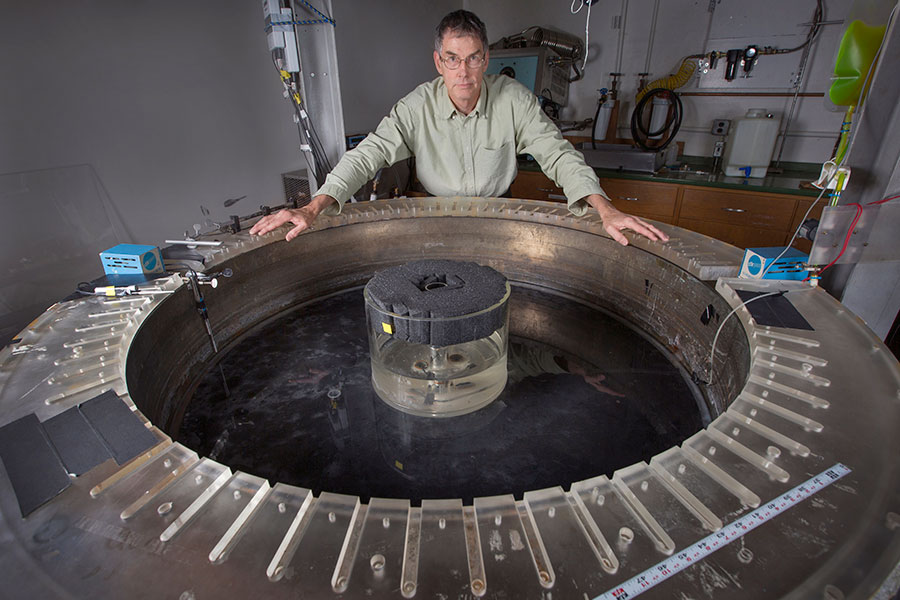

Many of these insights were derived from experiments conducted on a research instrument Speer refers to as the “big table” — a flat, circular apparatus that, when flooded with water, oscillated and heated at its center, simulates the effects of Earth’s rotation on the movement and circulation of large-scale planetary waves.

An instrument like the big table, which has facilitated so much consequential research and continues to aid scholars as they make groundbreaking discoveries, is singular among research institutes and exemplifies the prestige of the work produced by the GFDI, according to Speer.

“The big table is a very unique facility,” Speer said. “There are a couple of big rotating research tables in the world — there’s a very large one in Grenoble, France — but in terms of easily accessible laboratory research space, ours is one of the biggest on Earth. Many fundamental papers have come out of big table research that are still being acknowledged and referred to in new studies.”

With the help of the big table, other state-of-the-art research instruments and an inborn ethic of creative innovation, GFDI researchers have expanded the horizons of scientific inquiry.

Long-time GFDI researcher and FSU Professor Emerita Ruby Krishnamurti, for example, was among the first scientists to study the effects of double diffusion, the phenomenon of two properties diffusing at different rates in a medium. Krishnamurti’s pioneering research on double diffusion helped to explicate the process of ocean salt-fingering, which plays an outsized role in global climate regulation.

In addition, past GFDI scholars like Albert Barcilon and Louis Howard formulated theorems and conducted studies that have proved fundamental in the field and that continue to shape research of fluid dynamics throughout the global scientific community.

“The GFDI has an incredible heritage,” Speer said. “They were really the founders of the field.”

In its 50th year, the institute is not resting on its laurels.

The GFDI hopes to continue its legacy of leading from the front with plans to become one of the first programs in the nation to offer a doctoral program in fire dynamics and develop methods to accurately predict the onset of cold air outbreaks earlier than has ever been achieved reliably.

Crucial to that goal is attracting new cohorts of intelligent and enterprising undergraduate researchers to the labs and workshops that distinguish the GFDI as one of the premier research institutes in the region.

Tyler Bolles, a senior applied mathematics major who has conducted research on the nonequilibrium dynamics of water waves, said that the resources provided by the GFDI make the institute a dream for student researchers asking big and complicated questions.

While I am conducting experiments in the lab at GFDI on water waves, I see my work as more of an investigation of the nonlinear governing equations, which water waves happen to follow,” Bolles said. “The GFDI makes this research possible by providing me with the space and tools needed to carry out the experiment, as well as the technical support staff to help with problems I’m not well equipped to deal with on my own.”

Speer believes that a renewed focus on nurturing the success of undergraduate researchers like Bolles is essential in ensuring that the vital work done in the GFDI endures.

“I conducted research when I was an undergraduate, and I think it’s terribly important,” Speer said. “The GFDI is a great place for students who are inclined to scientific thinking and working with their hands. I want the future of the institute to include a rich undergraduate research culture.”