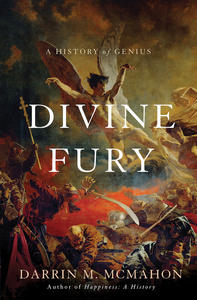

With 'Divine Fury,' history professor delves into two millennia of evolving perceptions of genius

Isaac Newton is universally recognized as one. So are Michelangelo, William Shakespeare and Albert Einstein. But what about Jimi Hendrix, Microsoft founder Bill Gates, or the dozens of people who receive MacArthur Foundation “genius grants” each year?

Darrin M. McMahon

Identifying and understanding the nature of genius is no simple task; tracking the evolution of the concept from antiquity to the present is exponentially more difficult. But that epic quest was recently undertaken by Darrin M. McMahon, the Ben Weider Professor of History in Florida State University’s College of Arts and Sciences. The acclaimed historian spent more than six years researching and writing his latest book of intellectual history, “Divine Fury: A History of Genius,” just published by The Perseus Books Group.

The first comprehensive history of the elusive concept, “Divine Fury” follows history’s greatest thinkers through the ages down to the present day, showing how — despite its many permutations — genius remains a potent force in our lives, reflecting modern needs, hopes and fears.

As with so much of Western culture, the quest begins during the period known as Classical Antiquity.

“The search for the origin of the concept of genius begins with the ancient Greeks, for whom being a genius was considered a form of madness,” McMahon said. “Plato, for example, described the great Athenian philosopher Socrates as ‘haunted,’ referring to his mental state. The first recorded use of the actual word ‘genius’ (then pronounced GAY-nius) by the ancient Romans was some 2,000 years ago. In their case, the word referred to the general divine nature that they believed was present in every individual man, place or thing.

Albert Einstein: A genius of the modern era

“The definition has changed dramatically over time and continues to be fraught with mystery and ambiguity,” McMahon said.

Jimi Hendrix: A rock 'n' roll virtuoso, yes, but was he a "genius"?

From the beginning of “Divine Fury,” McMahon sets a feverish pace in describing the god-given, tempestuous powers that were originally ascribed to the genius. An excerpt:

Even today, more than 2,000 years after its first recorded use by the Roman author Plautus, (the word “genius”) continues to resonate with power and allure. The power to create. The power to divine the secrets of the universe. The power to destroy. With its hints of madness and eccentricity, sexual prowess and protean possibility, genius remains a mysterious force, bestowing on those who would assume it superhuman abilities and godlike powers. Genius, conferring privileged access to the hidden workings of the world. Genius, binding us still to the last vestiges of the divine.

A more modern definition of genius — that of a startlingly exceptional human being — began to emerge during the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, McMahon said. Gone were the demigod-like figures of ancient times whose power derived from their role as divine intermediaries; in their place emerged individuals with their own power to create, to divine the secrets of the universe, to redefine the rules for art, science, statecraft and legislation.

“During the Enlightenment, geniuses came to occupy a space that lay precisely on the border between the human and the divine,” McMahon said. “Geniuses, that is, served a pseudo-religious function, supplanting in the collective imagination the higher beings — prophets, apostles, angels, saints — who had long served as intercessors between the human and the divine and who were now increasingly marginalized in a world experiencing the drama of disenchantment. Geniuses were seen as wondrous beings — prodigies of nature, entirely original and distinct — endowed with the capacity to see where ordinary mortals could not: into the fabric of the universe or the fabric of our souls.”

Assuming prominence in figures as varied as Benjamin Franklin, Isaac Newton and Napoleon Bonaparte, the Enlightenment’s conception of the genius emerged in tension with the era’s growing belief in human equality, McMahon says.

“Contesting the notion that all are created equal, geniuses served to dramatize the exception of extraordinary individuals not governed by ordinary laws,” he said. “The phenomenon of genius drew scientific scrutiny and extensive public commentary well into the 20th century, but it also drew religious and political longings that could be abused. The ‘cult of genius’ and pursuit of eugenics in Nazi Germany carried the concept of genius to a horrid extreme, leading to the traditional view of genius falling out of favor.”

Since World War II, the subsequent democratization of genius has led to its explosion as a “pop-culture trope,” McMahon says.

“Now anyone can be called a genius if they excel in their field. Rolling Stone magazine, for example, recently referred to rapper Kanye West as a ‘mad genius.’ But if everyone can be a genius, what does it even mean?”

McMahon’s rigorous scholarship won the highest of praise from Edward Gray, chairman of Florida State’s Department of History.

“Darrin McMahon is among the world's foremost historians of European intellectual life, and FSU is very, very fortunate to have him as part of its faculty,” Gray said. “Perhaps what most sets Darrin apart is the sheer scope of his work. In an age of intellectual particularism, when scholars typically toil within the confines of some narrow, highly specialized subject, Darrin casts his vision broadly. His newest book, ‘Divine Fury: A History of Genius,’ for instance, explores the history of this enormously vexed concept, from antiquity to the present, and it does so with an unusual combination of rigor and literary grace.

“I know of no other historian working in the United States, and perhaps even the world, who so consistently and successfully brings these qualities to bear on subject matter that is at once so expansive and so relevant.”

“Divine Fury” is McMahon’s second major work of intellectual history. His first, 2006’s “Happiness: A History” (Grove Press), took readers on a quest to define the philosophical nature and historical views of happiness, starting with Socrates and continuing up to modern times. Among other honors, the bestselling “Happiness” was named to The New York Times’ annual “100 Notable Books of the Year” list. Prior to that, his well-regarded history “Enemies of the Enlightenment: The French Counter-Enlightenment and the Making of Modernity” (Oxford University Press) was published in 2002.