Skipping high school physics can hurt collegiate performance across several majors

Enrollment in Florida’s high school physics classes has sharply declined over the last several years, damaging college preparation and performance, according to a Florida State University physics professor.

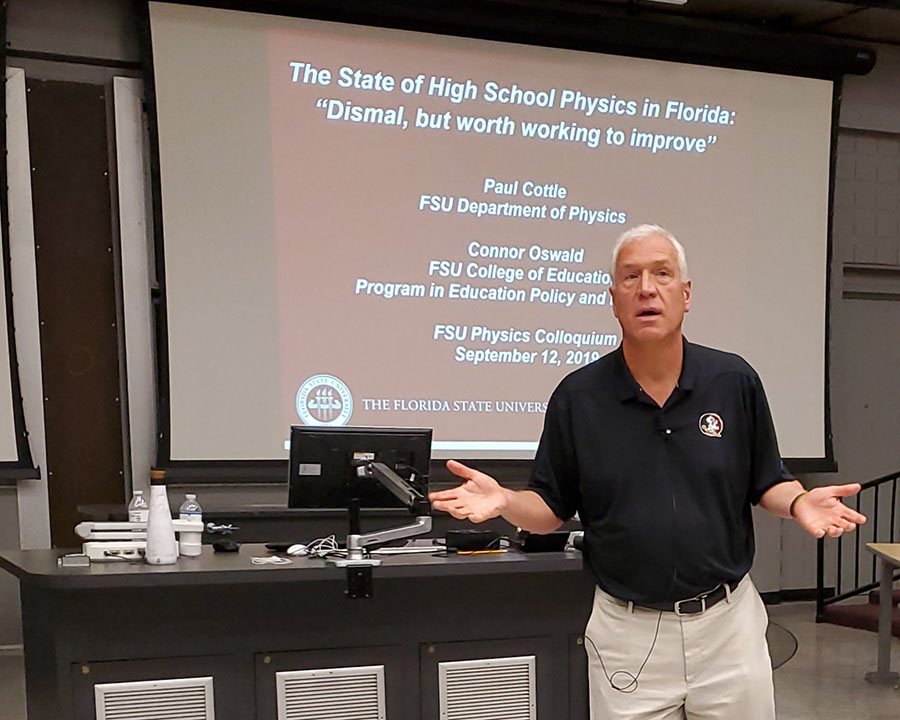

Speaking at the FSU Physics Colloquium, Paul Cottle, a member of Florida K-12 science standards committee in 2007-2008 and chair of the American Physical Society’s Committee on Education in 2013-14, said that from 2014 to 2018 physics class enrollment in the Florida’s public high schools dropped 12.2 percent. Without the necessary preparation in high school, he said, students are less likely to succeed in the collegiate math and science courses that ready them for careers post-graduation. In fact, students that elect not to take high school physics average a letter grade lower in college physics than those who do.

The lack of physics preparation affects students in a range of disciplines – degrees in life and health sciences, math, computer science, engineering and architecture all require or recommend the subject as part of degree requirements, Cottle said.

Across Florida, physics class enrollment rates vary dramatically by school district. Brevard County led the state with about 70 enrolled students per 100 12th graders, while dozens of other counties had single-digit enrollment in Fall 2018. High school physics enrollment also varies widely by state. Texas leads the nation, based on available data, with 80 percent enrollment, while Florida ranks in the bottom third with about 25 percent enrollment. The national average is estimated around 40 percent, but Cottle says educators know the formula to change those numbers.

“Enrollment is not determined by socioeconomic status; it’s determined by decisions made by adults running the schools and the school districts. If the adults think that physics is important, there will be physics courses,” he said.

Students competing for entry into Florida’s top universities may choose to forgo the challenging subject to avoid the risk of it lowering their GPA because physics is not required to graduate. Cottle has proposed wider-reaching solutions that could come at the state level, such as requiring physics coursework to earn Bright Futures scholarships or even admission to Florida State and University of Florida, but these have so far not gained momentum.

And for many communities, finding, preparing and keeping teachers in the STEM fields so courses can be offered is also an issue. Later during the colloquium, Connor Oswald, a graduate student in FSU's doctoral program for Education Policy and Evaluation, discussed his experience in the Jacksonville Teacher Residency Program, which aims to address high turnover rates among math and science teachers in the area’s resource challenged middle and high schools. Residents receive a stipend and guaranteed post-residency job placement while they earn a master’s degree in teaching from the University of North Florida and gain hands-on classroom experience.

Despite the program’s benefits, there are challenges in some of the classrooms. In his experience, Oswald was provided lab materials dated from as far back as 1959, while the most recent were from 2003. And, while his physics classes had 30 students, Oswald, who has a bachelor’s in physics and astrophysics from FSU, was also asked to teach marine science to as many as 46 students at a time. The lopsided student-to-teacher ratios, he said, are a key driver in staff retention, citing that five of the eight science teachers that started along with him had quit by the fifth week.

Oswald says he hopes to narrow his focus on finding ways to improve recruitment and retention of teachers and quality of physics instruction in the state’s high schools. The problem is not a new one: It’s something leaders in FSU-Teach, the university’s innovative interdisciplinary science and education program, have known for more than a decade as it has worked to address a critical shortage of teachers in biology, chemistry, physics, geosciences, mathematics, environmental science and now computer science through the mathematics area.

FSU-Teach, which aims to launch the next generation of math and science teachers, celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2018. Through this program, students pursuing undergraduate STEM degrees can earn a second major in secondary teaching at the same time without additional hours if they exchange electives for education courses. Since FSU-Teach’s implementation, nearly 40 institutions across the U.S. have added similar programs.

“We’re producing strong math and science teachers in that they know their content and they know how to teach it,” said FSU-Teach faculty member Cindy Dyar. “Administrators call me from around the state wanting to know how many graduates we have and would they be willing to go to their schools. Our teachers get snapped up right after graduation, sometimes before.”