Toy boats, Arctic ice and a science outreach success

But among their heavy coats and arsenal of research equipment, the team carried some unusual cargo: four cardboard boxes filled to the brim with more than 1,000 toy wooden boats, decorated by students and science enthusiasts from throughout the United States.

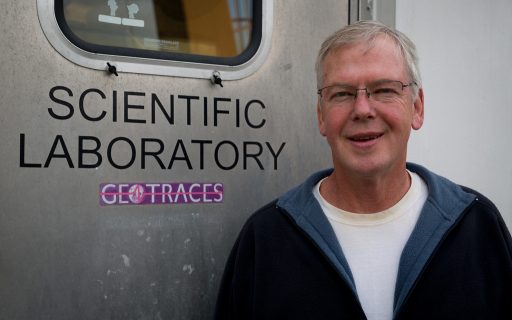

This peculiar payload was the product of an outreach initiative financed by a National Science Foundation grant awarded to Landing, who was the cruise’s co-chief scientist, and coordinated by U.S. Coast Guard Marine Science Coordinator Dave Forcucci.

The project, called Float Your Boat, called for the researchers to deposit the boxes full of toy boats on the ice floes that pave the bone-chilling North Pole in vast, stark white sheets. Each batch of boats was accompanied by a satellite buoy, so that Float Your Boat participants everywhere could track the tiny fleet as it drifted with the ice.

In October 2018, three years after the Arctic cruise, an Icelandic man named Bolli Thor found the first of the beached boats near his small home village.

“These are the coordinates, 63.962285, -22.734055, where I found one of your little wooden boats, near a small town called Sandgerði in Iceland where I live,” Thor wrote on the Float Your Boat website. “I found it at my favorite spot, where I usually walk with my dog called Tyra.”

More remarkable still, researchers were able to trace Thor’s boat back to the New York elementary school student who had adorned it with magic marker decoration years earlier.

“Being able to match the boat Bolli found to the student who originally decorated it was a huge surprise to all of us, given that there was almost nothing left on the surface of the boat except the www.floatboat.org stamp and some barely discernable hearts marked on the end of the boat,” Landing said. “The matching was done by colleague Tim Kenna. He distributed about 100 boats to students in and around New York City, and took lots of photos as the boats were loaded into the cardboard boxes to be lowered onto the ice.”

The dual purposes of the Float Your Boat project, a happy marriage of science outreach and investigation, allowed researchers to simultaneously generate excitement for their work and study the Arctic using unorthodox tools.

In an effort coordinated by Florida State researcher Peter Morton, almost three full boxes of the toy boats were decorated by attendees to the FSU-based National High Magnetic Field Laboratory’s 2015 Open House — a local hub for science outreach and community engagement. Later, Landing and his team, including the cruise’s co-chief scientist and Florida International University Professor David Kadko and University of Washington field engineer Paul Aguilar, found ways to use the boats as rudimentary scientific instruments.

“Once the boats fell into the water, they acted like drift cards, which allowed us to see where the surface currents took them,” Landing said. “The Float Your Boat project was a perfect opportunity to do something that was scientifically useful but can also have a major outreach impact.”

“The Float Your Boat program engaged not only the students who decorated their boats, but also the teachers, scout leaders and parents who were involved,” he said. “There is always a need to reach out to the public and help them understand the value of scientific research, especially these days when humans are having such a large impact on the environment.”

Landing said he hopes inquisitive beachgoers braving the chilly coastal weather in the Canadian Arctic, eastern Arctic and North Atlantic will continue recovering the small boats and reporting their discoveries.

Tyson Trudel with The Center of Wooden Boats in Seattle produced the toy boats, and Ignatius Rigor, a senior research scientist at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory, provided the tracking buoys.