Study: Warming global temperatures may not affect carbon stored deep in northern peatlands

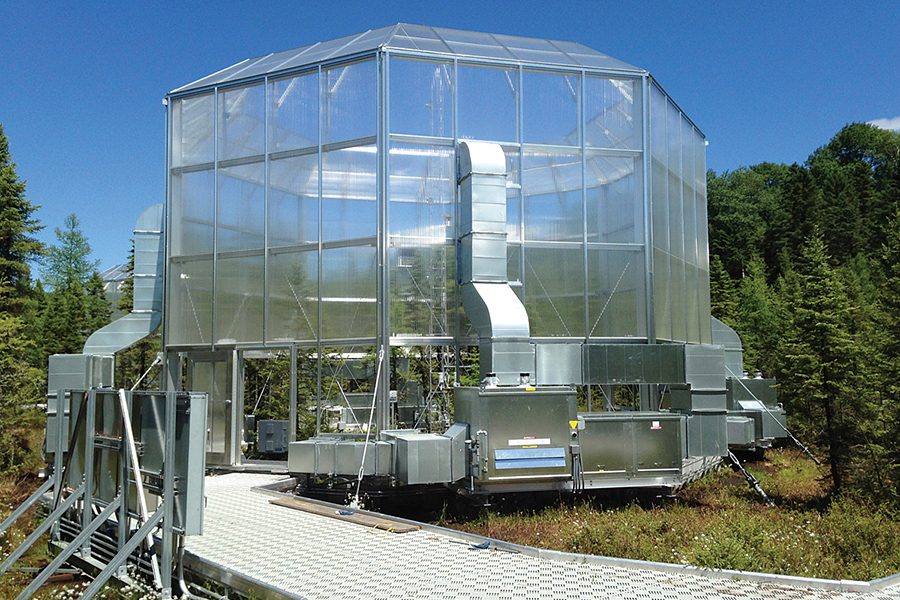

The SPRUCE research project is spread across seven acres in a natural spruce bog in northern Minnesota.

Image credit: Oak Ridge National Laboratory/U.S. Department of Energy

Deep stores of carbon in northern peatlands may be safe from rising temperatures, according to a team of researchers from several U.S.-based institutions.

And that is good news for now, the researchers said.

Florida State University research scientist Rachel Wilson and University of Oregon graduate student Anya Hopple are the first authors on a new study published today in Nature Communications. The study details experiments suggesting that carbon stored in peat — a highly organic material found in marsh or damp regions — may not succumb to the Earth’s warming as easily as scientists thought.

FSU Professor Jeff Chanton at

the SPRUCE research project

in northern Minnesota.

That means if these northern peatlands — found in the upper half of the northern hemisphere — remain flooded, a substantial amount of carbon will not be released into the atmosphere.

“We do see some breakdown of peat on the surface, but not below 2 feet deep, where the bulk of the carbon is stored,” Wilson said.

The study is part of a long-term look at how carbon stored in peat will respond to climate and environmental change. The team of researchers, led by Paul Hanson of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, includes scientists from FSU, University of Oregon, Georgia Institute of Technology, the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Forest Service, Chapman University, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Researchers ran four different temperature simulations — increasing the temperature of the peat by 2.25 degrees Celsius, 4.5 degrees Celsius, 6.25 degrees Celsius and 9 degrees Celsius — to see how it would respond to increased heat.

They found that the surface peat did emit more methane gas when warmed, but the deep peat did not break down and did not start emitting additional methane or carbon dioxide.

“If the release of greenhouse gases is not enhanced by temperature of the deep peat, that’s great news because that means that if all other things remain as they are, the deep peat carbon remains in the soil,” said Joel Kostka, professor of microbiology at Georgia Institute of Technology.

The open-topped enclosures—12 meters wide and 8 meters tall—sit over a corral bed that isolates the peatland.

Image credit: Oak Ridge National Laboratory/U.S. Department of Energy.

The Earth’s soils contain 1,550 billion tons of organic carbon, and 500 billion tons of this carbon is stored in northern peatlands around the world. This quantity is roughly the same amount as carbon in the atmosphere. Scientists have been anxious to learn how these northern peatlands will respond to warming because a tremendous amount of carbon could be released into the atmosphere, further fueling climate change.

Researchers worked at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s experimental site known as SPRUCE in northern Minnesota to examine both surface peat and peat up to 6 feet deep. The majority of the carbon is stored deeper in the ground.

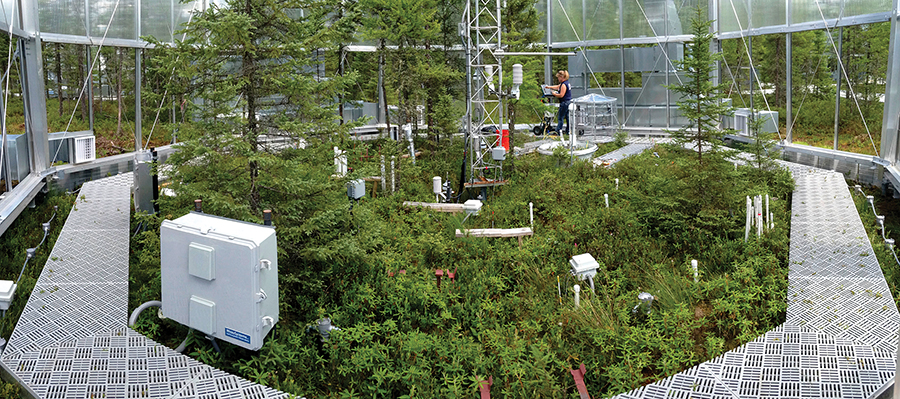

Large environmental chambers were constructed by the Oak Ridge team to enclose portions of the peatlands. Within these chambers, scientists simulated climate change effects such as higher temperatures and elevated carbon dioxide levels. They also took some of the deep peat back to their labs to heat in additional studies.

ORNL’s Jana Phillips measures surface CO2 and CH4 exchange in the back of a typical SPRUCE enclosure.

Image credit: Oak Ridge National Laboratory/U.S. Department of Energy.

While scientists said they were surprised by the findings, they also cautioned that they came after only one year of warming.

“There are the necessary caveats that this was only for one year, and the experiment is planned to run for a decade, and other ecosystem feedbacks may become important in greenhouse gas emissions,” said Scott Bridgham, director of the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at University of Oregon and Hopple’s adviser.

In the future, scientists plan to look at how these peatlands respond to heightened carbon dioxide levels combined with the temperature increases.

“In the future, we’ll be warmer, but we’ll also have more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, so we need to understand how these deep stores of peat, which have all this carbon, respond to these conditions,” said Jeff Chanton, professor of oceanography at Florida State University.

This work was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy.